L'Hôpital's rule

In calculus, l'Hôpital's rule pronounced: [lopiˈtal] (also sometimes spelled l'Hospital's rule with silent "s" and identical pronunciation), also called Bernoulli's rule, uses derivatives to help evaluate limits involving indeterminate forms. Application (or repeated application) of the rule often converts an indeterminate form to a determinate form, allowing easy evaluation of the limit. The rule is named after the 17th-century French mathematician Guillaume de l'Hôpital, who published the rule in his book Analyse des Infiniment Petits pour l'Intelligence des Lignes Courbes (literal translation: Analysis of the Infinitely Small for the Understanding of Curved Lines) (1696), the first textbook on differential calculus.[1][2] However, it is believed that the rule was discovered by the Swiss mathematician Johann Bernoulli.[3]

The Stolz-Cesàro theorem is a similar result involving limits of sequences, but it uses finite difference operators rather than derivatives.

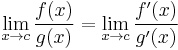

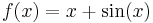

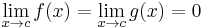

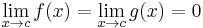

In its simplest form, l'Hôpital's rule states that for functions  and

and  :

:

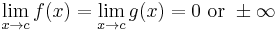

If

, and

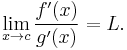

, and exists, and

exists, and on an open interval containing c,

on an open interval containing c,

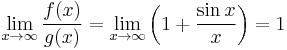

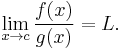

then

.

.

The differentiation of the numerator and denominator often simplifies the quotient and/or converts it to a determinate form, allowing the limit to be evaluated more easily.

Contents |

General form

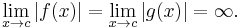

The general form of l'Hôpital's rule covers many cases. Let c and L be extended real numbers (i.e., real numbers, positive infinity, or negative infinity). The real valued functions f and g are assumed to be differentiable on an open interval with endpoint c, and additionally  on the interval. It is also assumed that

on the interval. It is also assumed that  Thus the rule applies to situations in which the ratio of the derivatives has a finite or infinite limit, and not to situations in which that ratio fluctuates permanently as x gets closer and closer to c.

Thus the rule applies to situations in which the ratio of the derivatives has a finite or infinite limit, and not to situations in which that ratio fluctuates permanently as x gets closer and closer to c.

If either

or

Then

The limits may also be one-sided limits. In the second case, the hypothesis that f diverges to infinity is not used in the proof (see note at the end of the proof section); thus, while the conditions of the rule are normally stated as above, the second sufficient condition for the rule's procedure to be valid can be more briefly stated as

Requirement that limit exist

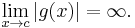

The requirement that the limit

exist is essential. Without this condition, it may be the case that  and/or

and/or  exhibits undampened oscillations as x approaches c. If this happens, then l'Hôpital's rule does not apply. For example, if

exhibits undampened oscillations as x approaches c. If this happens, then l'Hôpital's rule does not apply. For example, if  and

and  , then

, then

this expression does not approach a limit, since the cosine function oscillates between 1 and −1. But working with the original functions,  can be shown to exist:

can be shown to exist:

.

.

Examples

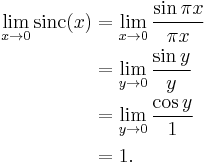

- Here is an example involving the sinc function and the indeterminate form 0⁄0:

- Alternatively, just observe that the limit is the definition of the derivative of the sine function at zero.

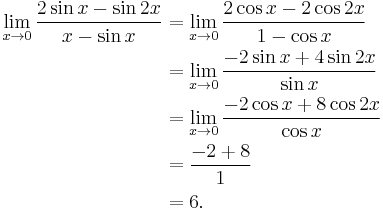

- This is a more elaborate example involving 0⁄0. Applying l'Hôpital's rule a single time still results in an indeterminate form. In this case, the limit may be evaluated by applying the rule three times:

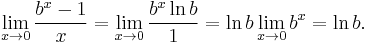

- This example involves 0⁄0. Suppose that b > 0. Then

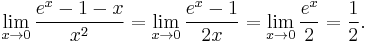

- Here is another example involving 0⁄0:

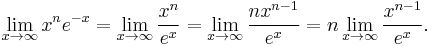

- This example involves ∞⁄∞. Assume n is a positive integer. Then

- Repeatedly apply l'Hôpital's rule until the exponent is zero to conclude that the limit is zero.

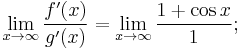

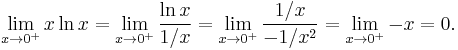

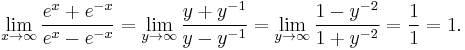

- Here is another example involving ∞⁄∞:

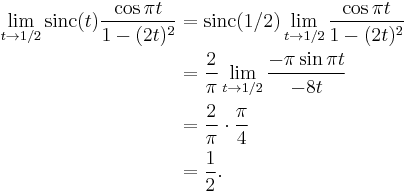

- Here is an example involving the impulse response of a raised-cosine filter and 0⁄0:

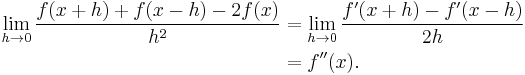

- One can also use l'Hôpital's rule to prove the following theorem. If f ′′ is continuous at x, then

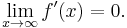

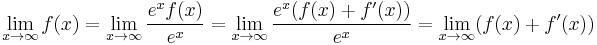

- Sometimes l'Hôpital's rule is invoked in a tricky way: suppose f(x) + f ′(x) converges as x → ∞. It follows:

- and so, if

exists and is finite, then

exists and is finite, then

- Note that the above proof assumes that exf(x) converges to positive or negative infinity as x → ∞, allowing us to apply L'Hôpital's rule. The results however still hold even though the proof is not entirely complete.

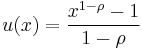

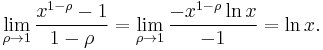

- L'Hôpital's rule can be used to find the limiting form of a function. In the field of choice under uncertainty, the von Neumann-Morgenstern utility function

- with

, defined over x>0, is said to have constant relative risk aversion equal to

, defined over x>0, is said to have constant relative risk aversion equal to  . But unit relative risk aversion cannot be expressed directly with this expression, since as

. But unit relative risk aversion cannot be expressed directly with this expression, since as  approaches 1 the numerator and denominator both approach zero. However, a single application of l'Hôpital's rule allows this case to be expressed as

approaches 1 the numerator and denominator both approach zero. However, a single application of l'Hôpital's rule allows this case to be expressed as

Complications

Sometimes l'Hôpital's rule does not lead to an answer in a finite number of steps unless a transformation of variables is applied. Examples include the following:

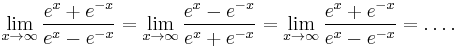

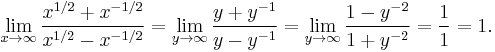

- Two applications can lead to a return to the original expression that was to be evaluated:

- This situation can be dealt with by substituting

and noting that y goes to infinity as x goes to infinity; with this substitution, this problem can be solved with a single application of the rule:

and noting that y goes to infinity as x goes to infinity; with this substitution, this problem can be solved with a single application of the rule:

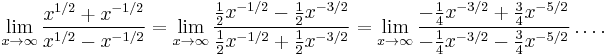

- An arbitrarily large number of applications may never lead to an answer even without repeating:

- This situation too can be dealt with by a transformation of variables, in this case

:

:

Other indeterminate forms

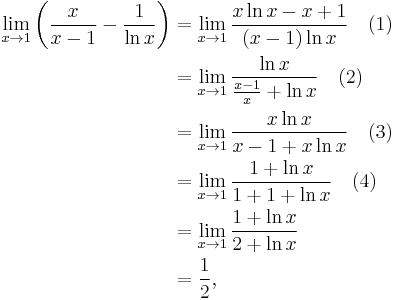

Other indeterminate forms, such as 1∞, 00, ∞0, 0 × ∞, and ∞ − ∞, can sometimes be evaluated using l'Hôpital's rule. For example, to evaluate a limit involving ∞ − ∞, convert the difference of two functions to a quotient:

where l'Hôpital's rule was applied in going from (1) to (2) and then again in going from (3) to (4).

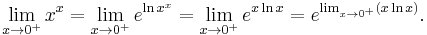

l'Hôpital's rule can be used on indeterminate forms involving exponents by using logarithms to "move the exponent down". Here is an example involving the indeterminate form 00:

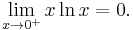

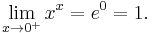

It is valid to move the limit inside the exponential function because the exponential function is continuous. Now the exponent  has been "moved down". The limit limx→0+ (x ln x) is of the indeterminate form 0 × (-∞), but as shown in an example above, l'Hôpital's rule may be used to determine that

has been "moved down". The limit limx→0+ (x ln x) is of the indeterminate form 0 × (-∞), but as shown in an example above, l'Hôpital's rule may be used to determine that

Thus

Other methods of evaluating limits

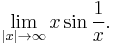

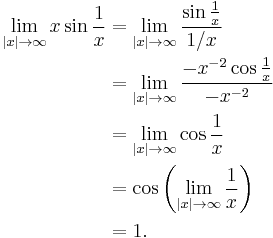

Although l'Hôpital's rule is a powerful way of evaluating otherwise hard-to-evaluate limits, it is not always the easiest way. Consider

This limit may be evaluated using l'Hôpital's rule:

It is valid to move the limit inside the cosine function because the cosine function is continuous.

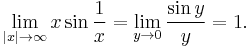

But a simpler way to evaluate this limit is to use a substitution. y = 1/x. As |x| approaches infinity, y approaches zero. So,

The final limit may be evaluated using l'Hôpital's rule or by noting that it is the definition of the derivative of the sine function at zero.

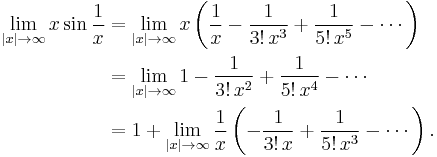

Still another way to evaluate this limit is to use a Taylor series expansion:

For |x| ≥ 1, the expression in parentheses is bounded, so the limit in the last line is zero.

Geometric interpretation

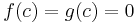

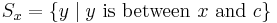

Consider the curve in the plane whose x-coordinate is given by g(t) and whose y-coordinate is given by f(t), i.e.

Suppose f(c) = g(c) = 0. The limit of the ratio f(t)/g(t) as t → c is the slope of tangent to the curve at the point [0, 0]. The tangent to the curve at the point t is given by [g′(t), f ′(t)]. L'Hôpital's rule then states that the slope of the tangent at 0 is the limit of the slopes of tangents at the points approaching zero.

Proof of l'Hôpital's rule

Special case

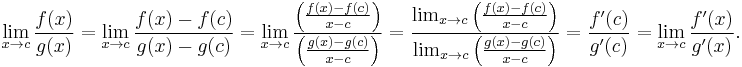

The proof of l'Hôpital's rule is simple in the case where f and g are continuously differentiable at the point c and where a finite limit is found after the first round of differentiation. It is not a proof of the general l'Hôpital's rule because it is stricter in its definition, requiring both differentiability and that c be a real number. Since many common functions have continuous derivatives (e.g. polynomials, sine and cosine, exponential functions), it is a special case worthy of attention.

Suppose that f and g are continuously differentiable at a real number c, that  , and that

, and that  . Then

. Then

This follows from the difference-quotient definition of the derivative. The last equality follows from the continuity of the derivatives at c. The limit in the conclusion is not indeterminate because  .

.

The proof of a more general version of L'Hôpital's rule is given below.

General proof

The following proof is due to (Taylor 1952), where a unified proof for the 0/0 and ±∞/±∞ indeterminate forms is given. Taylor notes that different proofs may be found in (Lettenmeyer 1936) and (Wazewski 1949).

Let f and g be functions satisfying the hypotheses in the General form section. Let  be the open interval in the hypothesis with endpoint c. Considering that

be the open interval in the hypothesis with endpoint c. Considering that  on this interval and g is continuous,

on this interval and g is continuous,  can be chosen smaller so that g is nonzero on

can be chosen smaller so that g is nonzero on  [4].

[4].

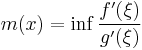

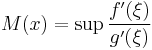

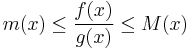

For each x in the interval, define  and

and  as

as  ranges over all values between x and c. (The symbols inf and sup denote the infimum and supremum.)

ranges over all values between x and c. (The symbols inf and sup denote the infimum and supremum.)

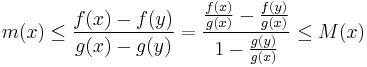

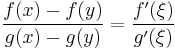

From the differentiability of f and g on  , Cauchy's mean value theorem ensures that for any two distinct points x and y in

, Cauchy's mean value theorem ensures that for any two distinct points x and y in  there exists a

there exists a  between x and y such that

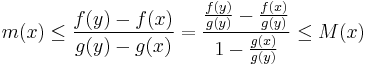

between x and y such that  . Consequently

. Consequently  for all choices of distinct x and y in the interval. The value g(x)-g(y) is always nonzero for distinct x and y in the interval, for if it was not, the mean value theorem would imply the existence of a p between x and y such that g' (p)=0.

for all choices of distinct x and y in the interval. The value g(x)-g(y) is always nonzero for distinct x and y in the interval, for if it was not, the mean value theorem would imply the existence of a p between x and y such that g' (p)=0.

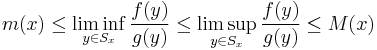

The definition of m(x) and M(x) will result in an extended real number, and so it is possible for them to take on the values ±∞. In the following two cases, m(x) and M(x) will establish bounds on the ratio f/g.

Case 1:

For any x in the interval  , and point y between x and c,

, and point y between x and c,

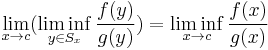

and therefore as y approaches c,  and

and  become zero, and so

become zero, and so

.

.

Case 2:

For any x in the interval  , define

, define  . For any point y between x and c, we have

. For any point y between x and c, we have

.

.

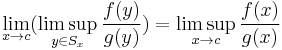

As y approaches c, both  and

and  become zero, and therefore

become zero, and therefore

The limit superior and limit inferior are necessary since the existence of the limit of f/g has not yet been established.

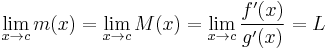

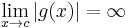

We need the facts that

and

and

and  .

.

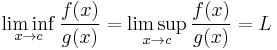

In case 1, the Squeeze theorem, establishes that  exists and is equal to L. In the case 2, and the Squeeze theorem again asserts that

exists and is equal to L. In the case 2, and the Squeeze theorem again asserts that  , and so the limit

, and so the limit  exists and is equal to L. This is the result that was to be proven.

exists and is equal to L. This is the result that was to be proven.

Note: In case 2 we did not use the assumption that f(x) diverges to infinity within the proof. This means that if |g(x)| diverges to infinity as x approaches c and both f and g satisfy the hypotheses of l'Hôpital's rule, then no additional assumption is needed about the limit of f(x): It could even be the case that the limit of f(x) does not exist.

In the case when |g(x)| diverges to infinity as x approaches c and f(x) converges to a finite limit at c, then l'Hôpital's rule would be applicable, but not absolutely necessary, since basic limit calculus will show that the limit of f(x)/g(x) as x approaches c must be zero.

See also

References

- Lettenmeyer, F. (1936), "Über die sogenannte Hospitalsch Regel", Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik 174: 246−247

- Wazewski, T. (1949), "Quelques démonstrations uniformes pour tous les cas du théorème de l'Hôpital. Généralisations" (in French), Prace Mat.-Fiz. 47: 117−128, MR0034430

Notes

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. "De L'Hopital biography". The MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. Scotland: School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews. http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/De_L'Hopital.html. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ l’Hospital, Analyse des infiniment petits… , pages 145-146: “Proposition I. Problême. Soit une ligne courbe AMD (AP = x, PM = y, AB = a [see Figure 130] ) telle que la valeur de l’appliquée y soit exprimée par une fraction, dont le numérateur & le dénominateur deviennent chacun zero lorsque x = a, c’est à dire lorsque le point P tombe sur le point donné B. On demande quelle doit être alors la valeur de l’appliquée BD. [Solution: ]…si l’on prend la difference du numérateur, & qu’on la divise par la difference du denominateur, apres avoir fait x = a = Ab ou AB, l’on aura la valeur cherchée de l’appliquée bd ou BD.” Translation : “Let there be a curve AMD (where AP = X, PM = y, AB = a) such that the value of the ordinate y is expressed by a fraction whose numerator and denominator each become zero when x = a ; that is, when the point P falls on the given point B. One asks what shall then be the value of the ordinate BD. [Solution: ]… if one takes the differential of the numerator and if one divides it by the differential of the denominator, after having set x = a = Ab or AB, one will have the value [that was] sought of the ordinate bd or BD.”

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W., "L'Hospital's Rule" from MathWorld.

- ^ Since g' is nonzero and g is continuous on the interval, it is impossible for g to be zero more than once on the interval. If it had two zeros, the mean value theorem would assert the existence of a point p in the interval between the zeros such that g' (p)=0. So either g is already nonzero on the interval, or else the interval can be reduced in size so as not to contain the single zero of g.

External links

- l'Hôpital's rule at PlanetMath

- Kudryavtsev, L.D. (2001), "L'Hospital rule", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=L%27Hospital_rule&oldid=14236

![t\mapsto [g(t),f(t)]. \,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/12c1e64fd84c6a461d37569359ccf14a.png)